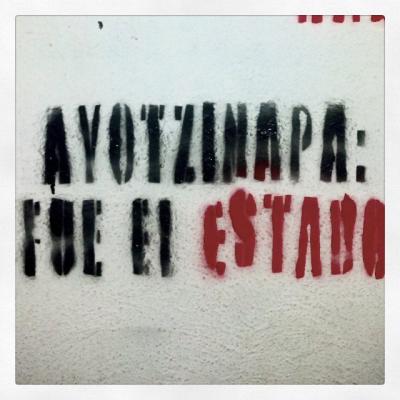

In the end, Ayotzinapa “was the State”, inasmuch as it was, and continues to be, the result of impunity and systematic abusive practices within the various levels of government in Mexico.

By Gema Santamaria. Published 9-25-2015 at openDemocracy.

One year has passed since 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Normal School in the state of Guerrero were disappeared by perpetrators whose identity remains unknown and whose crimes remain unpunished. The brutality attributed to the disappearance and alleged killing of the students, as well the covert and overt involvement of public officials and security personnel, put an end to the silence and inertia that seemed to had taken hold of Mexico.

Despite the several episodes of brutality and impunity shaking the nation over the last decade, including the mass killing of 22 civilians in Tlatlaya in the State of Mexico only two months before Ayotzinapa, no event had produced such a national sense of indignation as the disappearance of the 43 students. Ayotzinapa shattered at once the image of stability, cohesion, and economic modernization so carefully crafted by president Peña Nieto since the moment he took office in 2012. Ayotzinapa demonstrated that violence and insecurity were far from becoming an ancillary topic in the public agenda and that despite the government’s otherwise successful economic reforms, security and justice would continue to reflect the state’s incapacity to establish the rule of law.

Ayotzinapa expresses, perhaps in the most transparent and dramatic way, the legacies of a war on drugs that continues to loom large in the policies and politics of the Mexican state. It reveals the levels of corruptibility and criminal complicity that exist within different levels of government. It underscores criminal organizations’ increased capacity to both coopt and coerce state officials. It brings to the fore the abuses and human rights violations that have either been neglected or promoted by government officials in the name of security. It furthermore sheds light on the consequences of a set of policies that construed the lives of suspected criminals as less worthy to be subject to a system of due process and justice.

Without the visibility and public support that parents and friends of the 43 students have called upon, Ayotzinapa would be just one more amongst the 25 thousand anonymous and unpunished disappearances that have taken place in the country since the end of 2006. Without their names and faces standing at the forefront of street protests, local and international newspapers, and pro-human rights demonstrations, the 43 students would become yet another casualty in a war that has divided the nation between law-abiding citizens and those “others” whose killing could go unpunished.

Of course, the occurrence and ongoing impunity of Ayotzinapa signifies more than a legacy of the war on drugs. As a historian working on lynchings and extrajudicial killings in twentieth-century Mexico, I have been able to document firsthand a reoccurring theme of cases wherein state officials- from mayors to police officers and military personnel- participated in the torture and killing of individuals who were deemed politically dangerous. Against the image of a Mexican state that was able to build a “perfect dictatorship” through cooptation and limited repression, history shows that Ayotzinapa is part of a longer trajectory wherein political elites have tolerated and at times promoted the use of extrajudicial violence in order to establish their rule. Furthermore, political elites- at both the local and state level- have time and again used police forces as a means to advance their private interests and to establish alliances with certain criminal groups.

The networks of complicity between politicians, police forces, and criminal organizations underpinning the Ayotzinapa case are thus not new. Rather, they are the aggregated and aggravated result of a long and rather perverse exercise of authority that has contributed undermining the rule of law. Nonetheless, history does not simply repeat itself. Between the Mexico of the Ayotzinapa disappearances and that of the Tlatelolco massacre or the assassination of schoolteacher Lucio Cabañas, there are decades marked by social and political change. The vibrancy and maturity of Mexico’s civil society and the level of international scrutiny brought about by years of democratic struggle squarely situate Ayotzinapa in a historical present, wherein Mexican citizens and international actors are watching and willing to act.

The work of the Group of Independent Experts (GIEI by its Spanish acronym) designated by the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights, as well as the various demonstrations taking place in Mexico and other parts of the world throughout the past months, are illustrative of a new as well as emergent set of demands Mexican political elites face in regards to the nation’s sense of justice. They are also telling of the continuing contradictions that characterize Mexico’s system of democracy. The findings of the GIEI stress the inconsistencies and weaknesses of the investigation following the Ayotzinapa case. They furthermore suggest that the criminal complicity of security officials, at various levels of government, lies at the core of the case. In other words, it calls into question the “historical truth” articulated by the government and which had depicted Ayotzinapa as the product of a few local “bad apples,” rather than as the expression of systematic practices of abuse at all state levels.

Up until now, the Mexican government has remained open and in principle responsive to the demands of both civil society and international actors. Nevertheless, in practice, the investigation process has lacked both transparency and efficacy. The government’s “good intentions” have utterly failed to provide a sense of truth and justice that parents, students, and citizens alike continue to demand. Civil society, public opinion, and international players must remain vigilant and alert in order to bring justice to the Ayotzinapa students. Ayotzinapa is neither an isolated case nor one that can be subsumed under a narrative of drug-trafficking and “local” lawlessness.

Indeed, Ayotzinapa “fue el Estado,” inasmuch as it was and continues to be the result of impunity and systematic practices of abuse within different levels of government.

Omar García, one of the students that survived the attacks perpetrated that tragic night of September 26th of 2014, was asked in a recent conversation with university students in Mexico City to talk about the 43 disappeared. “How were they? What did they like to do? What soccer team did they supported?” asked candidly a student in an effort to bring their voices and lives back. Omar responded, pointing at different directions in the audience, “they were like you, and like you, and also like you.”

As long as we understand that Ayotzinapa is not an aberration that happens to “others,” as long as we regard it as a mirror and not simply a distortion of Mexico’s present reality, then we may be able to bring the 43 and the thousands of Mexicans who have been forcedly disappeared, back from oblivion and their disappearance, and closer to a sense of justice.

About the author

Gema Santamaría is an Assistant Professor in the International Studies Department of the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México. She holds a PhD in History and Sociology from the New School for Social Research.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.