Administrative decisions related to the country’s telecommunications policy often go unnoticed by the majority of the US citizenry. But now, net neutrality in its purest form is in peril.

By Michael J. Oghia. Published 3-17-2017 by openDemocracy

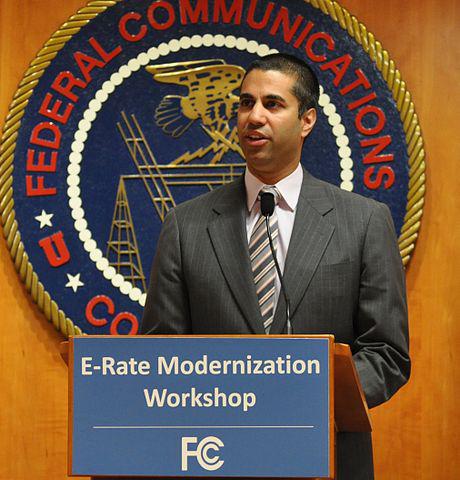

Welcome and Opening Remarks from Commissioner Ajit Pai, May 2014.Wikicommons/Federal Communications Commission.Public domain.

As this openDemocracy series has poignantly highlighted, digital rights should never be taken for granted. For all those keeping a close eye on US politics, this reality could not resonate more ominously. With the new Republican administration of Donald J. Trump, there is plenty of kindle to fuel a fire of discussion and, often enough, outrage.

Yet, behind all of the grandstanding, tweeting, and obscene showmanship, there lies a political machine forged in the corridors of Capitol Hill, skyscraping towers of corporate America, and musty legal libraries ready to take up the bureaucratic responsibility of running the United States. You see, outside of the more widely covered political issues such as immigration and healthcare, administrative decisions related to the country’s telecommunications policy often go unnoticed by the majority of the US citizenry.

Such is the case with the newly appointed chair of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Ajit Pai. A former Harvard and University of Chicago-educated legal counselor for Verizon, a major US telecom company, Pai was appointed as a commissioner in 2012 by former US President Barack Obama to join the five-member leadership team of the FCC – an independent government agency overseen by the US Congress that regulates the country’s communications policy. And to understand the new FCC under Pai, a member of the Republican Party, one has to understand Pai.

Pai is a staunch advocate against overregulation or intervention in what he considers blossoming markets, which he became known for during his tenure before being promoted by Trump to replace former FCC Chair Tom Wheeler. But he is better known for his opposition to Wheeler’s Open Internet Order. Taken together, his minimalistic regulatory philosophy, political leanings, and past history of opposing market intervention exemplify a new FCC chair that is in stark contrast to his predecessor – one that could have a lasting effect on net neutrality in the United States.

What is net neutrality?

Network neutrality is the principle that operators, including Internet service providers (ISPs), and government regulators should treat all Internet traffic (data) equally, not discriminating or charging differentially by user, content, website, platform, application, type of attached equipment, or mode of communication.

Coined by Columbia University media law professor Tim Wu in 2003, net neutrality is often considered a cornerstone of the open Internet that is paramount to safeguarding the fairness and equality of data traffic, as Washington Post tech reporter Hayley Tsukayama eloquently explained. Although it generally describes the debate surrounding whether or not Internet traffic should be regulated by governments, the term is often evoked to describe “throttling” by an ISP to slow Internet speeds in order to steer customers to services granted preferential treatment, such as by paying for faster speeds, or to manipulate a customer or service – such as what happened in January 2014 when the US broadband company Comcast severely crippled Netflix’s bandwidth and slowed their services to a crawl. As a result, Comcast demanded that Netflix enter into a preferential deal to peer with their network, thus creating a two-sided market for ISPs -– that is, a precedent grounded in data-specific traffic management (for a humorous account of this deal, see the Last Week Tonight with John Oliver segment that highlighted the effects it had on net neutrality in the US).

Moreover, net neutrality debates exist around the world. The European Union has particularly stringent net neutrality rules, which Luca Belli and Christopher Marsden covered in detail in this openDemocracy article in this same series, while this interactive map from the Global Net Neutrality Coalition offers a glimpse of absolute net neutrality protections by country. This form of net neutrality also garnered global attention in 2016 when the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) controversially banned Facebook’s Free Basics program citing net neutrality concerns. Pai, on the other hand, dropped FCC investigations into zero rating programs, arguing, “Free-data plans have proven to be popular among consumers, particularly low-income Americans, and have enhanced competition in the wireless marketplace.”

Retrieved from: http://knowmore.washingtonpost.com/2014/04/25/this-hilarious-graph-of-netflix-speeds-shows-the-importance-of-net-neutrality/

Is net neutrality regulation necessary?

Net neutrality is often a topic of conversation at Internet governance events I participate in, such as the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), and rarely does a digital policy issue present such a polarizing environment. Those who do not support absolute regulation – including Pai and Trump, economists such as Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker, technologists like one of the “fathers of the Internet,” Bob Kahn, senior managing director for global advanced technology policy at Cisco Systems, and former FCC chief of policy development, Robert Pepper, certain minority rights groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), telecom and cable providers such as AT&T, and technology companies providing over-the-top (OTT) services – generally advance one of seven arguments, including that net neutrality regulation deters investment into improving broadband infrastructure, and it provides government with more power over the Internet, undermining the free market. Absolute net neutrality opponents also argue that this regulation hurts consumers by limiting competition from bandwidth-intensive Internet-delivered services against traditional managed services, and impedes effective traffic management, which ISPs and especially wireless carriers require to maintain fast and efficient networks.

Those in favor of net neutrality regulation – including Bob Kahn’s “father of the Internet” counterpart, Vint Cerf, the founder of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, Internet service companies like Mozilla and Amazon, bloggers such as Matthew Inman from The Oatmeal, and digital rights groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), Public Knowledge, and Access Now – strongly advocate for net neutrality. They often argue that without such regulation, consumers will have little choice as to which services to use or the content they can access since ISPs would completely control Internet traffic, which they argue would lead to ISPs charging both consumers and Internet companies more for faster speeds and/or certain services and content. Additionally, pro-net neutrality proponents also fear that without regulation, small Internet companies would be shut out of mainstream service if they could not pay higher fees for greater bandwidth.

The future of the FCC and net neutrality in the United States

In February 2015, the FCC reclassified Internet service providers in the US so that it would be regulated as a phone-like common carrier as opposed to a mostly unregulated information system, which was upheld by a US Court of Appeals in June 2016. Fast-forward to the present, and Pai is reiterating his position that the FCC “made a mistake” regarding the Open Internet Order (in reference to the aforementioned regulatory policy). While this might seem alarmist, bear in mind that Google Chairman Eric Schmidt told a top White House official in 2014 that Obama was making a mistake by supporting strong net neutrality rules (Google’s net neutrality position is neither for nor against – it supports discrimination across different data types, such as health data versus streaming video, but not among similar data types).

Critics, however, have been quick to emphasize that under the FCC’s Open Internet Order, “Capital investments for large ISPs were nearly 9 percent higher than in the two years prior.” Moreover, a heavily referenced Free Press report also refuted the argument made by Pai that investment has “flatlined,” thoroughly documenting investment in Internet infrastructure in the US since the Open Internet Order was passed in 2015.

Regardless, though, net neutrality in its purest form in the United States is undoubtedly in peril. Although pro-net neutrality advocates have despaired over the possible death of US net neutrality in the past, highlighted its obsolescence, or at the very least, questioned the FCC’s intentions and decision-making process, the next four years will likely prove to be a tough time for them. As one member of an Internet policy email list I subscribe to wrote, “This retroactive step [rolling back net neutrality rules] will not spell well for the independence of Internet access to all concerned.”

Many of these concerns are grounded in the actions the FCC has taken since Pai became chair. In addition to scaling back transparency rules for smaller ISPs, and proposing to halt major new privacy requirements because they only target ISPs and not information services like Google, consumer advocates interviewed for a New York Times article stressed that Pai has “released about a dozen actions [since being appointed chair], many buried in the agency’s website and not publicly announced, stunning consumer advocacy groups and telecom analysts. They said Mr. Pai’s message was clear: The FCC … will mirror the Trump administration’s rapid unwinding of government regulations that businesses fought against during the Obama administration.” For instance, while they do not directly relate to net neutrality, Pai has also stopped nine companies from providing discounted high-speed Internet service to low-income individuals, withdrew an effort to keep prison phone rates down, and scrapped a proposal to break open the cable box market.

Yet, while “lighter” regulation was expected with the new administration, Pai’s intentions and actions are often demonized – even though he has maintained his desire to protect the “free and open Internet.” Pai has never criticized the concept of balanced net neutrality, and as one author writing for Forbes suggested, Pai’s FCC will be consistent, experienced, and professional – an apparent deviation from the administration as a whole. For instance, he introduced several new transparency measures to improve the public’s ability to view rules well before they are passed, unlike in the past where some rules were not published until well after their vote by the commission.

Moreover, according to Fast Company, “It seems less and less likely that Pai has it in mind to completely kill the network neutrality principles … [two commission insiders who insisted on anonymity said] Pai is more likely to scale back the effects of the order, rather than pushing the commission to withdraw it or asking Congress to pass legislation that overrides it. Pai may “soften” the order by allowing broadband carriers some kinds of web traffic prioritization or throttling under clearly defined conditions, one source said. For example, if a broadband customer is paying for 100 megabit-per-second broadband service, the provider might be allowed to prioritize some kinds of bandwidth-sensitive traffic (like video) in order to meet the speed promise.” In other words, the FCC’s new modus operandi vis-à-vis the Open Internet Order may likely offer ISPs more flexibility with traffic management, which deviates from the previous protocol under Wheeler of leaving data speeds untouched. The article concluded on an optimistic but also uncertain note: “For now at least, the reports of net neutrality’s death may indeed be greatly exaggerated.”

There is a case to be made that Pai is motivated by the firm conviction of operating within the limits of power/oversight granted to the FCC by Congress. Regardless of his intentions, though, he is expected to steer the FCC into “a more hands-off, pro-industry direction,” which was reinforced during his first US Senate hearing as FCC chairman on 8 March 2017. Time will tell whether or not his conviction – and his vision – will manifest in a way that protects the free, competitive, and open Internet he and many of his Republican colleagues advocate so adamantly for, or if it will lead to the fears some consumer advocates believe may come to pass: greater market capture/monopolization by the powerful, existing telecoms, and ultimately higher costs for US Internet subscribers.

Michael J. Oghia is an independent Internet governance consultant & editor based in Belgrade, Serbia. He was a two-time Internet Society (ISOC) ambassador the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), a fellow at ICANN58, and has lectured on Internet governance at the Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut (MDLAB). Twitter: @mikeoghia

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.