While most Native communities in Minnesota, such as the Ojibwe and others fighting pipeline projects through their land recognize that their fight for sovereignty is far from over, the land transfer to the Lower Sioux is a good, if small start in countering centuries of whitewashed history.

By Raul Diego Published 2-22-2021 by MintPress News

Image: Minnesota Historical Society

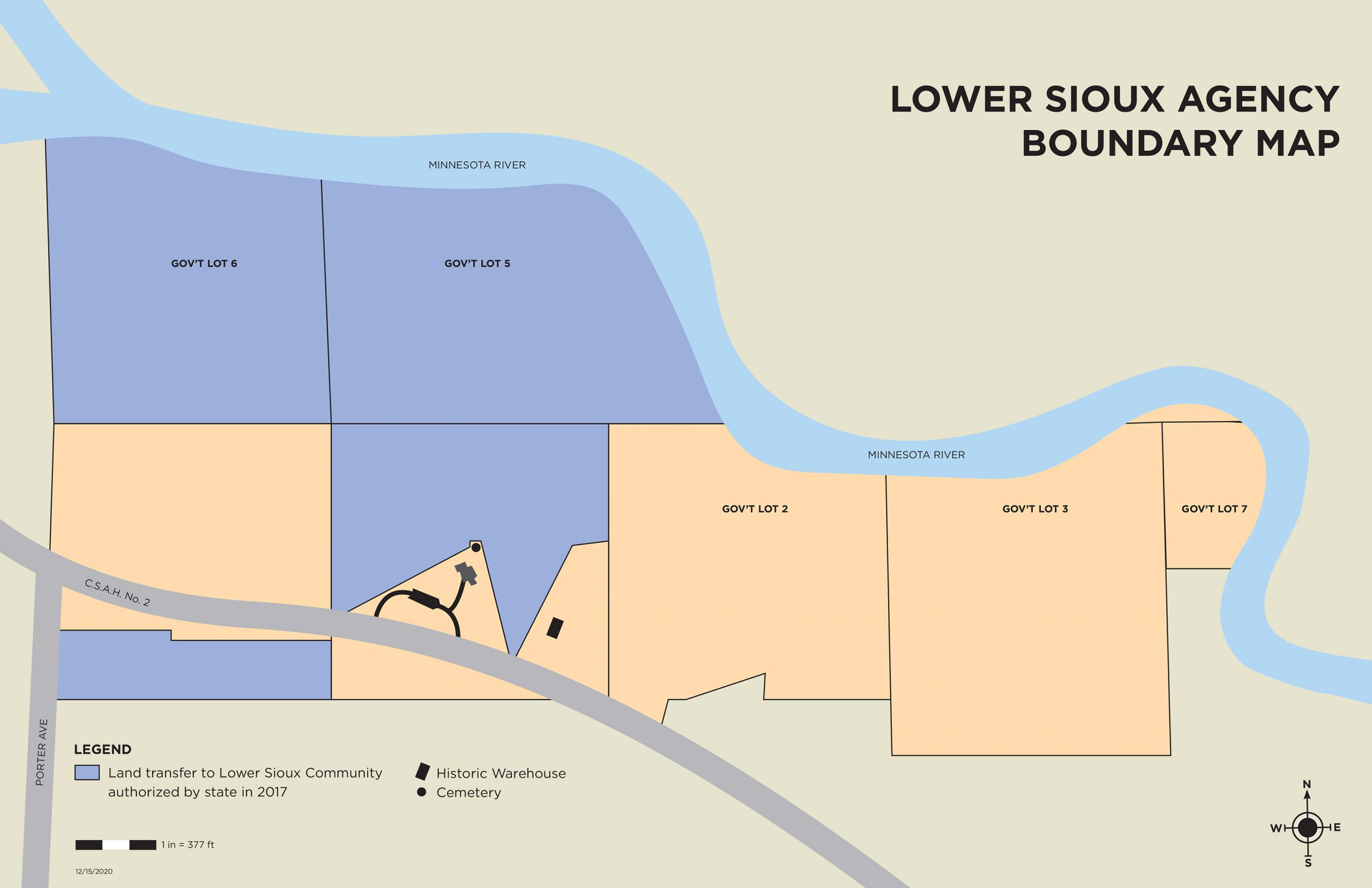

The state of Minnesota returned 114 acres of land to the Lower Sioux tribe after the final vote of the Minnesota Historical Society completed the last step in a four-year process that capped off a long fight by the sovereign Dakota nation to recover official title to their original home.

Mni Sota Makoce is the Dakota phrase that the name for “Minnesota” is derived from, which means Land Where the Waters Reflect the Clouds (or Cloud-tinted Waters). Incorporated as the thirty-second state of the Union in 1858, the ancestral home of the Anishinaabe and Dakota people saw the gradual arrival of French fur traders and loggers followed by other Western Europeans looking to make their fortunes mining for iron ore and exploiting other natural resources in a place settlers would later describe in the much more banal terms “land of ten thousand lakes” in tourism brochures of the early twentieth century and embossed on the state’s license plates since the 1950s.

The difference in how each called the vast territory exposes the cultural and spiritual discrepancies that simmer at the core of every conflict between Native populations and the European invaders of North America.

In Minnesota, a century of skirmishes and broken treaties would erupt in what is known as the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 between the incipient federal government of the United States and the Native Dakota. The brief, yet bloody conflict, would change the course of history and lead to a 30-year period of First Nation genocide across the Western and Southern parts of the country, including mass internment of women and children and the forced displacement of entire Native communities through the so-called Trail of Tears.

More than 150 years later, the government of Minnesota is walking back some of those traumatic events by returning 114 acres of land to descendants of the people who were forcibly removed from their homeland.

The Lower Sioux Tribe is one of the 11 federally-recognized sovereign tribes in Minnesota and the original inhabitants of the region, which they call Cansa’yapi – “where they marked the trees red”. Lower Sioux Community Council President Robert Larsen stresses that the transfer is “not a sale” and highlights the fact that his Sioux ancestors “paid for this land over and over with their blood, with their lives”.

Taking the land back

The historic transfer had been approved by the Minnesota State Legislature in 2017 and had been in the process of clearing the necessary procedures, such as environmental impact assessments, to execute the final conveyance that took place earlier this month. Larsen, who represents the approximately 1,000 enrolled members of the Lower Sioux, expressed his wish that the action will allow them to “try to reclaim that relationship with the land and hopefully we can continue the healing.”

Among the things Larsen and others hope the transfer will help to achieve is the revival of the disappearing Dakota language, which has been enjoying a resurgence thanks to classes offered to middle and high school students in the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation. In addition, the language has also been placed on the curriculum as a high school-level credit course in Southern Minnesota.

The ten other tribes that make up the remainder of the broader Dakota community are also part of a larger effort to restore Native American culture and traditions, which Dennis Olson Jr., executive director of Minnesota’s Indian Affairs Council, says is a part of a national trend.

According to Olson, “language revitalization” programs administered through the institution have received increased funding since 2010 and at least $2.4 Million have been allocated to “Indian immersion schools” through the state’s Legacy Amendment funding program.

The land transfer, however, is just a drop in the bucket for Larsen, who hopes that it is “just a kick-start to showing people that it can be done.” 130 acres of the total area that is part of Cansa’yapi Oyate is still owned by the state and managed by the private Minnesota Historical Society (MHS). Lamenting that “local farmers [still] have more land than the tribe”, Larsen hopes for a greater share of the territory would require legislative approval and a review by the State Historic Preservation Office.

A path towards healing

At the very least, the partial land return opens the door to a long-overdue rapprochement between the United States government and the original inhabitants of the land that was stolen from them. Flandreau Santee Sioux member Kate Beane and director of Native American Initiatives at MHS is confident that the action is “more than symbolic” and can lead to “actionable things that some agencies and organizations can do to help support the healing.”

The wounds are deep, as attested to by the hanging of the 38 Dakota men Abraham Lincoln sentenced to death in the largest mass execution in U.S. history as a direct consequence of the five-week war at Cansa’yapi Oyate in 1862 – an act which, has been commemorated by Dakota tribal members in a 330-mile journey on horseback from Lower Brule to the site of the execution in Mankato Minnesota for the last 15 years.

Beyond the significance of returning 114 acres of land to its rightful owners, there is also a matter of cultural recognition that must be addressed. While most Native communities in Minnesota, such as the Ojibwe and others fighting pipeline projects through their land recognize that their fight for sovereignty is far from over, the land transfer to the Lower Sioux is a good, if small start in countering centuries of whitewashed history like the “charming” tales of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s childhood in Minnesota’s early settler days, that many Americans know through the TV show Little House on the Prairie. Settler accounts like these should always be accompanied by the stories of Little Crow and how he avenged his people’s starvation and death at the hands of Ingalls Wilder’s progenitors at Cansa’yapi Oyate, setting off the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

A deeper appreciation of the other is the only possible path towards healing. For centuries, Native Americans have been trying to communicate their pain to the White man, like Chief Wabasa did to the first Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota, Henry Whipple, when the latter seemed bothered by the “foolish dances” of the Dakota youth. “It is because their hearts are sick,” Wabasa responded, “They don’t know whether these lands are to be their home or not.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.