We’ve talked a lot about the devastating impact the oil boom we’re experiencing currently is having on the environment. We’ve talked about oil spills, exploding trains, earthquakes and miscellaneous other effects. Now, there’s another damaging byproduct that’s made the news in the last few days; saltwater spills.

What does saltwater have to do with drilling for oil? Water below the freshwater table becomes more salty with depth, and water injected into the ground during fracking operations can become salty before it rises back towards the ground. This briny water comes up with the oil, and must be separated or removed, and may be 20 to 30 times as salty as seawater. There’s two common ways of disposing of the brine: 1) wastewater injection, which is linked to increased earthquake activity in numerous states; most notably Oklahoma, and 2) storage in an evaporation tank/area, where the residues can be buried in a landfill.

Spills are common in this process. 141 brine water pipeline spills were reported in North Dakota alone in 2012, and a 2006 rupture that spilled 1 million gallons into a creek, aquifer and pond is still being cleaned up.

Which brings us to three recent spills in North Dakota. On June 27, a saltwater disposal facility near Ross was struck by lightning. Authorities let the storage tanks burn down before putting out the fire. 580 barrels of oil and 1,800 barrels of saltwater were spilled. Then, on July 7, 11 tanks (9 saltwater and 2 oil) on an oil site in McKenzie County were destroyed in a lightning strike and subsequent explosion. Over 2,000 barrels of saltwater were spilled, as well as 167 barrels of oil.

Then, on July 8, a leak was discovered in an underground pipeline near Bear Den Bay, a tributary of Lake Sakakawea when company officials were investigating reports of production shortfalls. By the time the leak was discovered, over 1 million gallons (24,000 barrels) of saltwater had been spilled. Why did it take so long to discover? Because the pipeline doesn’t have a system to send an alarm in the event of a leak or rupture.

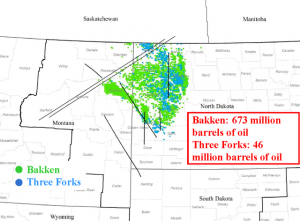

Lake Sakakawea, a reservoir on the Missouri River, provides water to communities on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, occupied by the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara tribes. But, the reservation is the source of more than 30% of the state’s 1 million barrels of oil produced per day, according to the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources.

The EPA said yesterday that they were trying to determine if the saltwater had reached the lake or not; but they were fairly confident that most of the saltwater had was pooled on the ground, soaked into the soil and held back by dams. Cleanup of the site is estimated to take weeks.

Company and tribal officials claimed that the spill was contained, but there was visible damage from the spill. Kris Roberts, an environmental geologist with the North Dakota Department of Health, said; “We’ve got dead trees, dead grasses, dead bushes, dying bushes.”

The more we see of the peripheral damage done by the waste products of fracking, not to mention the oil spills and explosions, the more we realize what a self-destructive path we’re following in our thirst for oil. What we need is a renewable energy program along the lines of the industrial switch to a wartime economy during World War II. Not only will future generations thank us, but it’s more likely that there will be future generations if we do.