A reconstruction of the events surrounding the disappearances of the 43 Mexican students has highlighted the mistakes authorities commit. Sadly, we may never get to the bottom of what really happened.

By Manuella Libardi. Published 9-26-2017 by openDemocracy

Credit: Forensic Architecture.

The third anniversary of the the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College students (known as normalistas) in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico has come and has brought new developments with it.

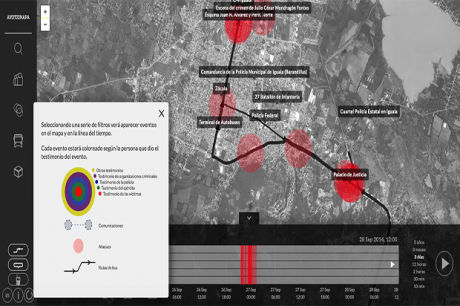

Forensic Architecture, a London-based agency that conducts research on behalf of international prosecutors, human rights organizations, and political and environmental justice groups, has reconstructed the events of Sept. 26 and 27, 2014, which is presented as a forensic tool for parents, investigators and the general public to further the investigation. The interactive platform depicts a vivid account showing federal and state police agents in the vicinity at the moment when 43 students disappeared from Iguala.

FA pieces together the events of 26 September 2014, when about 100 normalistas were attacked in the town of Iguala, Guerrero, by local police in collusion with criminal organizations. Numerous other branches of the Mexican security apparatus either participated in or witnessed the events, including state and federal police and the military. Five people, including two students and a minor, were killed when the officers opened fire on the buses, and another student was later found dead, his body showing signs of horrific torture. Forty other were wounded, and 43 students simply vanished.

FA’s main sources of evidence are the reports produced by the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI, by its initials in Spanish) – which was created in November 2014 through an agreement between the Inter American Court of Human Rights (IACHR), the Mexican State, and representatives of the disappeared students in Ayotzinapa – whose findings point to several wholes in the official investigations and raises several questions, all of which the government has chosen to ignore.

GIEI found that there were nine separate attacks between that Friday and Saturday in different places. This shows the scope and magnitude of operation that simply doesn’t match the authorities’ narrative. Also, the involvement of different police departments, including municipal, civil, and federal shows a level of coordination that suggest coordination at the central, or federal, level. Everything remains very confusing, but the FA reconstruction of events shed new light on the events of that night.

Forensic Architecture reconstruction

Photo: Isabel Sanginés/SomosDelMedio.Org (Flickr). Some rights reserved.

FA highlights five major shortcomings in the official investigations. First, the version of events the Office of the General Prosecutor presented in court fails to meet the evidence. This version confuses places, suppresses relevant scenes and events, confuses the times, and presents events that are physical impossible to have happened the way prosecutors described, just to name a few. The Office continues to defend this version of events, last present before a judge in December 2014, to this day. This version of events is so unsustainable that Forensic Architecture argues that “many of the defendants will easily be able to reverse the accusations eventually”, meaning that “the negligence in the investigation may cause that the Ayotzinapa case goes unpunished”, according to its report. The agency also found that the Office obtained confessions and declaration through “questionable methods”, such as coercion, which not only violates human rights, but also prevents the truth from surfacing.

Second, the Office of the General Prosecutor failed to properly interrogate the Military Intelligence Agent who reported to the commander of the Mexican Army’s 27th Battalion based in Iguala and witnessed the main attack against the students for almost an hour, even taking videos and photos. The evidence reconstructed by FA shows that the agent was at the exact place and time as the “fifth bus”. The final GIEI report found that the hundred or so students were traveling in a convoy of five buses, though the “fifth bus” inexplicably disappeared from the official case files at some point during the investigation. FA also found that the Military Intelligence Agent ran from the Iguala Municipal police, leaving a civilian motorcycle behind. The report contends the Mexican Army then went back to the scene to retrieve the motorcycle used irregularly by the Agent and not to look for the missing students.

Third, the FA report sustains that, similarly to the Military Intelligence Agent and Federal Police officers, the regional coordinator of the Guerrero’s Ministerial Police was also present at the time the students went missing. This piece of information is relevant given the alleged Ministerial Police’s role in the violent persecution of the surviving victims of the attacks. Additionally, the Ministerial Police’s has been publicly accused of having ties to organized criminal organizations, as well as the Iguala Police, claims that have not been adequately investigated.

Fourth, the FA was able to reconstruct the visual field, which shows a witness never identified by the Office of the General Prosecutor. Also, neither the Office of the General Prosecutor nor the Office of Guerrero’s Prosecutor timely requested the surveillance footage from security cameras installed on the courthouse’s exterior walls, which could have included valuable evidence. Later, the Supreme Court of Justice destroyed this footage.

Lastly, Forensic Architecture points out that the need to clear up what happened at “Crucero de Santa Teresa”, where a sixth bus carrying soccer players from a Chilpancingo team, which had nothing to do with the Ayotzinapa Normal School, also came under deadly attack that night as it tried to leave Iguala. Even though this attack is unrelated to the normalistas, understanding what happened there is key to understanding why local police were stopping buses in Iguala. The events around this sixth bus could hold valuable information regarding the motives and the underlying cause behind the attacks.

But why?

A memorial for the 43 missing students. Photo: Semoan80, CC BY-SA 4.0.

A government investigation soon concluded that the police – in the pay of a local drug gang called Guerreros Unidos – mistook the students for members a rival drug gang known as Los Rojos. But Mexicans were – justly – skeptical of this finding. Mexico’s former Attorney General Jesús Murillo Káram determined that the 43 normalistas were taken to a dumping ground in Cocula to be burned and that their ashes were later thrown to a river. Human rights, legal, and medical experts have consistently questioned these conclusions, and, thus the case remains open.

Additionally, the government claimed the students had gone into Iguala to boycott a political speech by the mayor’s wife. But evidence shows the students had not even intended to go there. They had originally intended to commandeer more buses in the state’s capital city, Chilpancingo, but decided to detour when they found federal police patrol cars near the toll booths where they were to intercept the buses. These makes both government’s theories – that the students had political motives and/or relation to a drug gang that had come to challenge the dominant local gang, Guerreros Unidos – unsustainable.

One hypothesis regarding the motive behind the attack gained momentum about a year after the events and argued that the police were not after the students, but their bus. Speculations center on the idea that the bus was carrying shipment of drugs and/or money, which corrupt officers were trying to recover. This hypothesis suggests that the students were at the wrong place at the wrong time and that authorities, upon realizing their mistake, covered up the facts and tried to pawn it off as a gang-related operation gone awry.

The truth is, we may never get to the bottom of what happened and, like FA predicts, perpetrators may go unpunished. But none of this means that Ayotzinapa will stop fighting for their own. Less than two weeks ago, 60 students seized a bus to demand truth and justice for the 43 missing students. Local police opened fire at the bus and arrested 12 students, reflecting an attitude all to familiar to the residents of the small rural town.

About the author

Manuella Libardi is a Brazilian journalist with a Masters in International Relations. She is currently an IBEI intern at democraciaAbierta.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.