An abandoned oil tanker with over a million barrels of oil on board is an environmental catastrophe waiting to happen.

By Chris Baraniuk. Published 2-18-2020 by openDemocracy

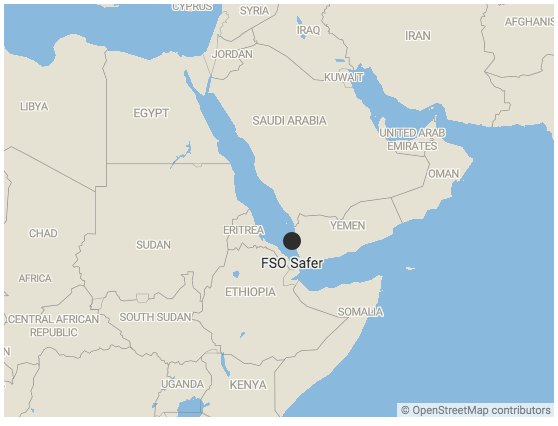

he FSO Safer is moored five nautical miles off the coast of Ras Isa on Yemen’s west coast. | Image: Conflict and Environment Observatory

Five miles off the coast of Yemen lies a floating bomb. An oil storage vessel called the FSO Safer has been sitting more or less unattended in the Red Sea for half a decade.

A victim of Yemen’s current civil war, the Safer has fallen in to a dire state of disrepair, with rust spreading around her hull and on-board equipment. She is packed with more than a million barrels of crude oil, which over time is thought to have steadily released flammable gases meaning the Safer could explode if she doesn’t simply begin leaking huge volumes of oil into the sea.

That would cause a huge environmental catastrophe – one that would affect the lives of millions of people in the region. How did this ship end up in such a sorry state?

The FSO Safer was built in 1976 in Japan and for roughly 10 years sailed the world’s oceans as an oil tanker. In 1987, she was converted into a stationary storage facility for the Safer oil company and brought to an offshore position near the Yemeni coast. With a total capacity of three million barrels of oil, the Safer became a useful but not particularly special bit of infrastructure.

When war broke out in Yemen in March 2015, few people gave the vessel much thought. It and many other assets owned by the same firm were quickly seized by Houthi rebels. But unlike land-based installations and pipelines, the Safer now finds itself in an especially precarious predicament. Sitting in the sea, it is corroding away rapidly as we speak.

The FSO Safer sits five miles off Yemen’s west coast | Map created with Datawrapper.

The conflict in Yemen has proved to be both long and complicated, with no end in sight. The internationally-recognised government in the country, which is currently supported by Saudi Arabia, has no access to the Safer because the vessel remains under Houthi control. Analysts say the Houthis are using the Safer as leverage.

“They consider it as a hostage and they want to keep it because they can threaten the coalition forces in the Red Sea,” says Yemeni economic researcher Abdulwahed Al-Obaly.

Al-Obaly is an employee of the Safer company. He says that the FSO Safer was due to be replaced by a land-based storage facility years ago but the project was never completed. By 2015, millions of dollars a year were being spent on maintenance costs racked up by the vessel, says Al-Obaly. He explains how the explosive gases that build up in the Safer’s storage tanks over time would periodically have to be vacuumed off. Since civil war broke out, little or no maintenance has been carried out.

“Any kind of ship that sits in the sea or moves around in the sea has to be regularly maintained,” says Laleh Khalili, professor of international politics at Queen Mary University London.

In the absence of constant sanding and painting of the hull, the Safer has essentially been left to rot. And while Prof Khalili notes that tankers caught in the midst of past conflicts in the region have been known to leak oil before, the volume of crude on the Safer puts it into a league of its own.

“That makes it a lot more of a concern,” she says.

The Houthi strategy of using the Safer as a bargaining chip is potentially disastrous. If gases on board were to ignite, experts fear they could cause a gigantic explosion deadly to any individuals or shipping in the vicinity at the time. Plus, the Red Sea is a particularly salty body of water, meaning that the Safer’s hull is corroding faster than it would elsewhere in the world.

But it gets worse. The 1.15m barrels of oil on board is Marib Light, a type of crude that mixes more easily with water, explains Dr David Soud at IR Consilium, a maritime security consultancy that has been tracking the FSO Safer situation.

Should that oil begin to flow out of the rusting hull and into the Red Sea, it could form a spill roughly four times as large as the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989 – and with crude that mixes down into the water column.

“It will not be the kind of spill that will settle on the bottom or simply on the top,” Dr Soud says.

That means the Safer presents a significant threat to nearby coral reefs, marine life and also desalination plants in the region that provide drinking water to nearby countries including Saudi Arabia.

There were fears that a spill had begun last December but these proved to be unfounded, according to satellite imagery analysed by Samir Madani, co-founder at TankerTrackers.com. There is still no sign of a major leak unfolding, he adds.

“Honestly though, she’s a ticking time bomb. The UN needs to tend to that situation ASAP,” he says.

The United Nations has been involved in efforts to neutralise the situation and attempted to organise an expedition to board and assess the vessel last year. However, such an inspection has still not taken place. The Safer was raised in a recent meeting of the Security Council but no public action has yet followed.

Al-Obaly is among those who have criticised the UN’s response to the situation. The UN did not respond to a request for comment from openDemocracy.

Experts are not only worried that natural decay will spell doom for the vessel. It is also possible that she could be openly attacked by an aggressor seeking to target nearby facilities or tip the balance of power in the area. It would be something of a nuclear option, perhaps, but conflict in the region is notoriously unpredictable.

The FSO Safer may not be viewed as a top priority in Yemen, never mind the Middle East as a whole, which faces a multitude of challenges. However, those sounding the alarm from afar think that the risk posed by the Safer is so great that it cannot be ignored any longer. They also argue that, should access to the vessel be granted, it would not be overly difficult to extract oil from her and virtually eliminate the threat of catastrophe.

“Frankly, it’s painful. It is frustrating as hell to watch […] a preventable crisis that could lead to greater conflict not be addressed when it is eminently doable,” says Dr Ian Ralby at IR Consilium.

And there are some who, despite the personal risks involved, are chomping at the bit to tackle the problem.

John Curley is a salvage specialist who once worked for the United Nations Development Programme. He was involved in the salvage and removal of ships from Iraqi ports during the Iraq war. If the Houthis were to grant access to the Safer, he says the operation to deal with the ship would be fairly straightforward.

“Basically, once the green light is given we’d move onto location. We’d assess the condition on deck and find out the condition of the oil and the amounts,” he says.

If the ship were seaworthy, it could be towed to port where oil on board could be pumped away, he adds. Alternatively, if the Safer could not be towed, the oil could be removed at sea and relocated.

Removing the oil would involve drilling through the hull on either side of the vessel, below the waterline, and using divers or remotely operated vehicles to attach underwater “umbilical cords”. These would suck out the beleaguered cargo to fill barges waiting nearby.

“That way you will empty the full capacity of each tank [in the vessel] in the safest way possible,” says Curley.

If this or some other remedial operation is not carried out, there’s no doubt that a catastrophe will eventually occur, says Dr Ralby. “It’s not a question of ‘if’, it’s merely a question of ‘when’,” he says.

The sticking point may ultimately be the Houthis – will they or won’t they grant access, and under what terms? It has been reported that they have demanded $80m in return for the Safer’s oil in the past. That sounds like a lot of money but given the severity of the threat facing marine life and human populations in the region, some argue it is a levy worth paying.

“If the catastrophe happens, even billions of dollars will not be enough to sort out the problem,” says Al-Obaly.

While various parties fret or argue over what to do with the Safer, there she sits in the Red Sea with many thousands of tons of oil on board. A giant problem begging to be fixed – waiting, rusting, creaking.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.