Written by Rahul Telang. Published 2-25-2016 by The Conversation.

The ongoing fight between Apple and the FBI over breaking into the iPhone maker’s encryption system to access a person’s data is becoming an increasingly challenging legal issue.

With a deadline looming, Apple filed court papers explaining why it is refusing to assist the FBI in cracking a password on an iPhone used by one of the suspects in the San Bernardino shooting. CEO Tim Cook has declared he will take the case all the way to the Supreme Court.

The tech company now wants Congress to step in and define what can be reasonably demanded of a private company, though perhaps it should be careful what it wishes for, considering lawmakers have introduced a bill that compels companies to break into a digital device if the government asks.

But there is an irony to this debate. Government once pushed industry to improve personal data privacy and security – now it’s the tech companies who are trumpeting better security. My own research has highlighted this interplay among businesses, users and regulators when comes to data security and privacy.

For consumers, who in coming years will see ever more of their lives take place in the digital realm, this heightened attention on data privacy is a very good thing.

The business case for better privacy grows

Not too long ago, everyone seemed to be bemoaning that companies aren’t doing enough to protect customer security and privacy.

The White House, for example, published a widely cited report saying that the lack of online privacy is essentially a market failure. It highlighted that users simply are in no position to control how their data are collected, analyzed and traded. Thus, a market-based approach to privacy will be ineffective, and regulations were necessary to force firms to to protect the security and privacy of consumer data.

The tide seems to have turned. Repeated stories on data breaches and privacy invasion, particularly from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, appears to have heightened users’ attention to security and privacy. Those two attributes have become important enough that companies are finding it profitable to advertise and promote them.

Apple, in particular, has highlighted the security of its products recently and reportedly is doubling down and plans to make it even harder for anyone to crack an iPhone.

Whether it is through its payment software or operating system, Apple has emphasized security and privacy as an important differentiator in its products. Of course, unlike Google or Facebook, Apple does not make money using customer data explicitly. So it may have more incentives than others to incorporate these features. But it competes directly with Android and naturally plays an important role in shaping market expectation on what a product and service should look like.

These features possibly play an even more critical role outside the U.S. where privacy is under threat not only from online marketers and hackers but also from governments. In countries like China, where Apple sells millions of iPhones, these features potentially are very attractive to end users to keep their data private from prying eyes of authorities.

Regulators hum a different tune

It is clear that Apple is offering strong security to its users, so much so that FBI accuses it of using it as a marketing gimmick.

It seems we have come a full circle in the privacy debate. A few years ago, regulators were lamenting how businesses were invading consumers’ privacy, lacked the proper incentives to do so and how markets needed stronger rules to make it happen. Today, some of the same regulators are complaining that products are too secure and firms need to relax it in some special cases.

While the legality of this case will likely play out over time, we as end users can feel better that in at least in some markets, companies are responding to a growing consumer demand for products that more aggressively protect our privacy. Interestingly, Apple’s mobile operating system, iOS, offers security by default and does not require users to “opt-in,” a common option in most other products. Moreover, these features are available to every user, whether they explicitly want it or not, suggesting we may be moving to a world in which privacy is fundamental.

Data sharing gets complicated

At its core, this debate also points to a larger question over how a public-private partnership should be structured in a cyberworld and how and when a company needs to share details with either the government or possibly with other businesses for the public good.

When Google servers were breached in China in 2010, similar questions arose. United States government agencies wanted access to technical details on the breach so it could investigate the perpetrators more thoroughly to unearth possible espionage attempts by Chinese hackers. The breach appeared to be aimed at learning the identities of Chinese intelligence operatives in the U.S. that were under surveillance.

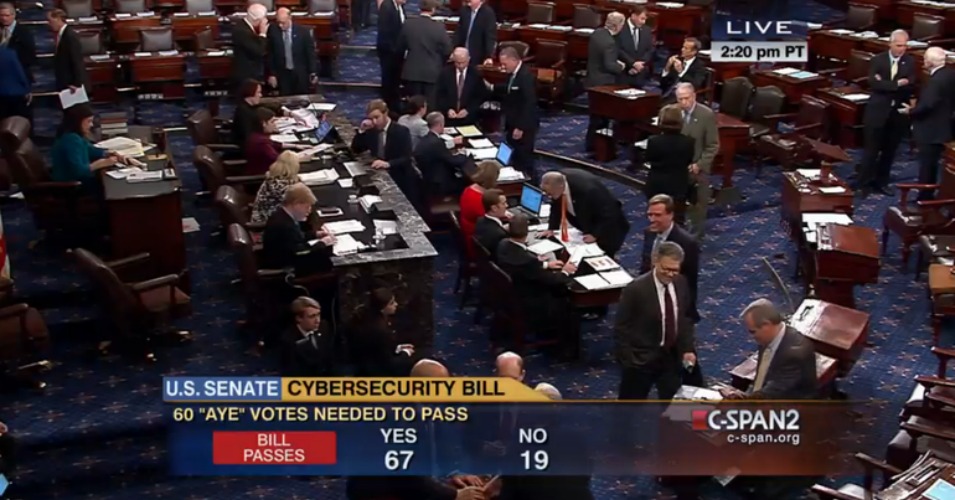

Information sharing on data breaches and security infiltration is something the government has widely encouraged, last year passing the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act of 2015 to encourage just that.

Unfortunately, various government agencies themselves have become self-interested parties in this game. In particular, the Snowden disclosures revealed that many government agencies conduct extensive surveillance on citizens, which arguably not only undermine our privacy but compromise our entire information security infrastructure.

These agencies, including the FBI in the current case, may have good intentions, but all of this has finally given profit-maximizing companies the right incentives they need to do what the regulators once wanted. Private businesses now have little incentive to get caught up in the bad press that usually follows disclosures like Snowden’s, so it’s no wonder they want to convince their customers that their data are safe and secure, even from the government.

With cybersecurity becoming a tool for government agencies to wage war with other nation-states, it is no surprise that companies want to share less, not more, even with their own governments.

The battle ahead

This case is obviously very specific. I suspect that, in this narrow case, Apple and law enforcement agencies will find a compromise.

But the Apple brand has likely strengthened. In the long run, its loyal customers will reward it for putting them first.

However, this question is not going away anywhere. With the “Internet of things” touted as the next big revolution, more and more devices will capture our very personal data – including our conversations.

This case could be a precedent-setting event that can reshape how our data are stored and managed in the future. But at least for now, some of the companies appear to be – or least say they want to be – on our side in terms protecting our privacy.

About the Author:

Professor of Information Systems and Management, Carnegie Mellon University.