Many Kurdish towns across Turkey lie in ruin, but Yüksekova — a bulwark of the PKK — has so far escaped destruction. Still the war is always present

By Alex Kenman. Published 3-8-2016 by ROAR Magazine

Egid called me today to tell me that the situation in his hometown is rapidly deteriorating. It’s been nine months since I last saw him in Yüksekova, or Gever in Kurdish, in southeastern Turkey.

Egid is a positive man. Despite the hardships he and his people face on a daily basis, he has the capacity to enjoy life to the fullest wherever he is. Actually, it may well be that it is precisely because of those hardships that he is so positive, as a sort of self-preservation mechanism. Violence, repression and uncertainty are common themes in his daily life.

On July 20, 2015, Süleyman, a 25-year-old teacher, was killed together with 32 other primarily Kurdish activists in the Suruç suicide attack. Two days later, when his body was brought to Yüksekova, the whole city shut down. Hundreds of cars filled the main highway to show their respect and thousands of people attended the funeral.

I often envy him for his positive attitude. With him, any ordinary situation would turn into something special; whether we would be secretly drinking beers at night in his cousin’s van, or simply having a chat over a cigarette in the kitchen. He has learned to appreciate and accept life the way it is.

Egid often calls me to cheer me up, when by all means it ought to be the other way around. He tells me how I should feel blessed to live in such fortunate circumstances.

But this time it was different.

He called to say he had lost all hope. He seemed upset, explaining that while he and his family are okay right now, he doesn’t know what will happen in a few weeks’ time. They are expecting the Turkish military to come soon, after the snow has melted, to do to Yüksekova what they already did to Cizre, Sur, Sirnak, Nusaybin and all those other places: “To wipe out all terrorists.” They fear they will be trapped inside their houses, with no food, medical care, media, or observers, and that they will risk getting killed whenever they step outside. In English this situation is translated as a “curfew”, but that’s not the right word to describe the situation. It’s a military siege.

The distribution or possession of PKK magazines like this may lead to imprisonment and terrorist charges. Nevertheless, they remain popular throughout Yüksekova, a center of resistance.

Yüksekova, just like Cizre, is one of those towns infamous for its decades-long resistance. The PKK has always been very popular here, and it still is. Referring to Yüksekova and the surrounding Hakkari province, Abdullah Öcalan once said, “This is where we are strongest.” Indeed, beyond the military outposts this territory is ruled, or at least strongly contested, by the PKK.

From here, Qandil — where the guerrilla’s headquarters are based — is only a stone’s throw away, on the other side of the border between Turkey and Iraq. Traditionally, Spring is when the fighting starts, as the snow-capped mountains become a little bit more accessible, both for the Turkish army and the PKK.

It is in Hakkari where one can come to a true understanding of what the Kurdish struggle is all about. The ever-present conditions of the ongoing war are impossible to ignore, and it inevitably maneuvers its way into all aspects of daily life.

This sports hall was set on fire during a protest. Governmental buildings are often set on fire as they are easier targets than police and military buildings.

Yüksekova has thus far escaped the fate of many other towns and cities across Bakur, or North Kurdistan. Egid’s family’s house is still safe, for now, but guarantees are a scarce commodity in these critical times. If the Turkish military attacks, the people of Yüksekova will resist fiercely, that much is sure.

Back in 2013, Egid feared that if the peace process were to come to an end, the war would erupt like never before. He saw the youth around him, the next generation, and realized that they were much more radicalized than him. So much so that these youngster appeared to be willing to fight to the very end. This is what the region has witnessed with the YDS, the so-called “Civil Protection Units”, made up of heavily armed and radicalized youths.

In the people’s experience, the situation now is worse than it was at the height of the conflict in the 1990s. People are desperate, and every time it seems impossible for things to get worse, the conflict is escalated to a whole new level.

A VICIOUS CYCLE OF VIOLENCE

One night in August we sat in front of Cihan’s house, one of Egid’s friends. We smelled the teargas and tried to discern the different loud bangs in the distance. Were they explosions, gunfire, or something else? We tried to figure out what was going on, but with the internet not working and the media silenced, this proved an impossible task. Cihan said that things hadn’t been this bad in years, that there’s often the sound of gunfire but not for three hours straight, as happened that particular evening.

Some say there are so few birds left in Yüksekova because they all died from the teargas, which fills the air of the town on a regular basis. Ironically this has created a metal recycling business among kids to earn some money.

We were lucky this time, because the fighting often takes place right next to the house. The traditional thick walls of the house have too often proven their necessity as bulletproof entrenchment.

The sound of gunfire and whiffs of teargas that reached us were only the whispers of the war that was taking place around us, but they carried with them the fear for the well-being of friends and family elsewhere in the town.

Cihan is from a politicized family. His younger brother has just been released after five years in jail. His father had been in prison for ten years, and many of his uncles and cousins are still locked up, while others are with the guerrilla forces in the mountains.

Sahit never says goodbye. He isn’t accustomed to it, because in prison you never leave. He was imprisoned at the age of 15, as a preventive measure. It would be 17 years before he was eventually released. “The world changed. It was a new world, I felt like aliens had landed. When I left there were one or maybe two televisions in the whole city. Now everyone had one. Most of all, I left as a child, but I didn’t realize I had grown up. Society had changed and I didn’t know how to cope with it.”

Rojda’s family originally came from Iran, their grandfather was a famous revolutionary who fought the Shah in Iranian Kurdistan. They fled when her husband would risk a death sentence in Iran. In Turkey he was betrayed, and served a long time in jail. Her youngest son has been in prison too. When he went on hunger strike together with many fellow Kurdish prisoners in 2012 to ask for more rights, she joined in solidarity.

Cihan’s brother tells about the first night of their father’s imprisonment. They put him in a certain position, one thumb bound to the ceiling in such a way that he could just reach the floor with his toes. The prison guards laughed “Welcome! This is just your first night, we’ll be easy on you”. Cihan’s father still has a problem with that thumb.

They tortured the man for a month. For ten years he was imprisoned. When he came back he was a mere shadow of the man he used to be. He would not join family dinners, and although his smile never left his face he became a very distant person. His world consists of the house and the front yard — the outside world is something he can’t handle.

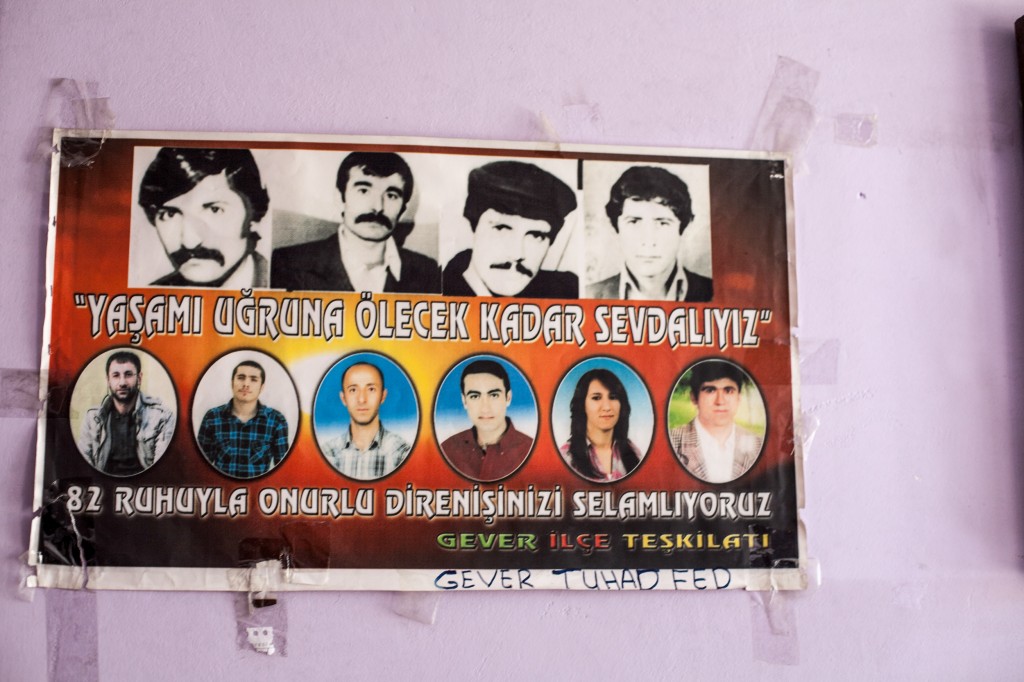

“We love enough to die for the sake of life.” Above, Mehmet Hayri Durmuş, Kemal Pir, Akif Yılmaz, Ali Çiçek started a hunger strike until death in 1982 in Diyarbakir prison. The people at the bottom row were also on long hunger strikes.

Each of the rooms in the house has a television. At least one was always on. Apparently it eased his mind. However, when the situation throughout Turkey started to escalate, Cihan’s father became more restless. The news was all about the latest clashes and the question that was on everyone’s mind: “Will there be war?”

The present situation that has been going on for so long is about whole generations and entire cities being traumatized; about daughters and sons getting killed, brothers and sisters imprisoned. Despite all that, even while for a moment even Egid lost his hope, he picked himself up and said: “It doesn’t matter, we will win. We will teach them the reality is right, unavoidable. You were there! You are my friend and you took all these pictures. Maybe one day you will show them.”

They came at midnight. First they went to the wrong house. We were away doing construction work, and came home late in the night. They took him violently. We don’t know when he will be released. My oldest son is a guerrilla, he joined at his seventeenth, he is 22 years old now. I haven’t seen him for almost six years. My imprisoned son was photographed at a protest. It was unfair.

They came through the garden in the middle of the night, and broke our door and windows. They aimed a gun at my daughter’s head. They searched everything and then took my son. They beat him with sticks, they beat him in front of us. They tortured him for eight days, until he had a heart attack. He had to go to the hospital.

He was 18 or 19 when they took him. It’s been ten months now. They accused him of killing three soldiers. The thing is, it’s all a lie. The killers have already been arrested, and the court says he’s not guilty. Still, they keep him. Next month there will be another court case.

We were still awake as we just came back from work. Around 3am the special forces came. They tried to break open the door. I opened it and asked what they wanted. They just rushed in and aimed their gun at my little boy. When I shouted “don’t do that!” they put me on the floor, face down, and broke my finger. They also attacked my neighbor and broke three of his teeth.

My son was sleeping, they arrested him. Later they came back with him, they wanted the gun. There wasn’t a gun. I swear to allah, we do not have a gun. They started beating my son. My son was very angry. They kept beating him. We can actually forgive them. We just want our son back.