As evidence of UN peacekeepers’ sexual violence against Black African women and girls grows, media reporting and research reinterprets this as ‘transactional sex’, through the logic of colonialism.

By Guilaine Kinouani. Published 11-25-2016 by openDemocracy

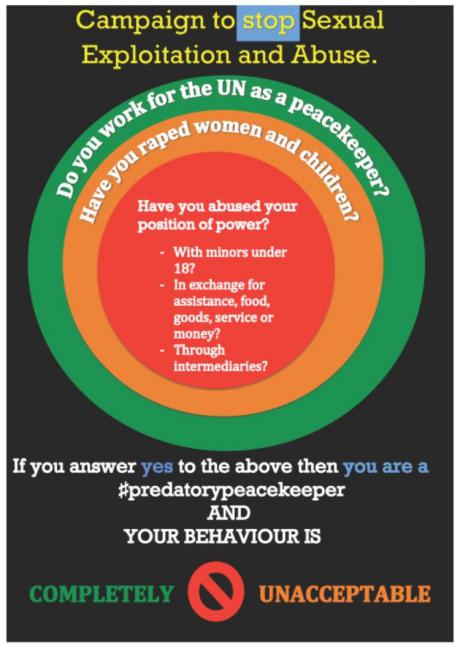

Photo:: Predatory Peacekeepers

A few months ago, the campaign #predatorypeacekeepers started on social media. It followed a report from a Canadian AIDS charity accusing UN and French troops in the Central African Republic (CAR) of sexually abusing at least 98 girls. The damning report alleged that three girls had been tied up and forced to have sex with a dog, that one of the victims subsequently died and that many of the abuses were orchestrated by a French General. Since publication, more victims have come forward. Many spoke of degrading sexual acts including soldiers urinating on the victim’s body or in her mouth.

Allegations of sexual misconduct by UN soldiers have been documented in most of the countries where UN peacekeeping troops serve. However, what seems striking in CAR is the alleged involvement of senior officers and the age of the victims. In December 2015, an Independent Panel produced scathing findings on the way the UN had responded to the allegations in CAR. It identified systematic failures and highlighted a culture of impunity, inadequate investigatory mechanisms and unsatisfactory structures to support victims. There has been no public update by the UN on the progress made in implementing the recommendations of the Panel. The few prosecutions have exclusively been of (Black) African Peacekeepers. White predatory peacekeepers, it appears avoid accountability.

‘Transactional sex’ and fallacy of consent

Both social and legal definitions of rape are centred, if only partly, on the notion of consent. One way to nullify rape is to establish consent or to effectively blur its boundaries. This is achieved in relation to the victims of predatory peacekeepers when sexual relations between Black/African women and UN soldiers are described as transactional. In ‘transactional sex’, one party gets sexual access to another person’s body in exchange for gifts and/or other goods. As there is a material gain (usually for the women) consent is thus deemed to be present. Any quick internet search reveals that the media has been awash with headlines of transactional sex.

‘UN peacekeepers ‘barter goods for sex’

U.N. peacekeeping and transactional sex

Reporting sex in exchange of goods, and luxury goods and/or mobile phones, in particular does more than imply consent. It invites public judgements around the morality of the victims and, reproduces ‘misogynoirist’ associations between black womanhood and materialism. This taps into implicit prejudices and bias and reduces cognitive dissonance. The last link above, by Cage, refers to a research project conducted in 2012 on the prevalence of this so called ‘transactional sex’ in Monrovia (Liberia) during the civil war. The study estimates that 58 000 women aged between 18 and 30 had engaged in ‘transactional sex’ with UN personnel at some point and that over half were below 18 on the first occasion. Despite this, the words rape or consent are notably absent in this piece. Similarly, allegations in Haiti involved children but again media reports of ‘transactional sex’ were written with no reflection on the presumption of consent.

Photo:: Predatory Peacekeepers

Age differences are a major source power differential, which is just one of the reasons why sexual offences against minors are specified in most penal codes. Given that such offences exist in most nations it is extraordinary that the potential that such acts might be sexual abuse of children is rarely broached. In addition to age, a number of contextual constraints should lead to questions about the validity of consent.

The power differentials – social, legal, institutional and even symbolic – between the Black/ African women and UN soldiers create a number of barriers to their capacity to give meaningful consent. Differences in ‘social class’ and geo-political positioning, in race, in emotional vulnerability – let’s not forget we are talking about women in war or otherwise environmentally precarious zones – soldiers’ holding and/or having access to heavy artillery and guns, each and cumulatively make consent impossible to give freely. Presumably, it is for these reasons that the UN banned its peacekeepers from engaging in ‘transactional sex’.

Whiteness and the rape-ability of Black/African girls and women

An intersectional approach is needed to grasp the particular sexual subjugation of Black/African women by western or western commissioned men, and the media’s apparent determination to impute consent onto them. It also avoids a decontextualized account which unwittingly reproduces violence in ways central to the white patriarchal colonial order: here African and Black woman appear as inferior and subordinated, yet that very subordination is rendered invisible. This process normalises gendered and racialised violence whilst making it impossible to name whiteness as the key underlying structure.

But, whiteness is engaged here. It is engaged in the structural invisibilisation of the Black/African victims and in the failure to hold white perpetrators to account. It is engaged in the presentation of Black bodies as sites for white expressions of sadism and sexual perversion, and in the reproduction of gendered racialised hierarchies. The social construction of Black women’s sexuality as ‘promiscuous’ and depraved has a long colonial history which continues to lead to an unwillingness, conscious or otherwise, to protect black girls/women’s bodies from sexual assault and rape.

At the core of our presumed suitability for violent sexual consumption or rape-ability, is not only our constructed hyper-sexuality but also ideas of dirt and impurity – markers of course of our inhumanity – victims of predatory peacekeepers could be perversely sexually violated and soiled (with urine) because their bodies were deemed impure. This implicit responsibility is both the cause and effect of their worthlessness. And so, sexual contact with men constructed as superior, as noble saviours willing to touch the Black body, cannot possibly be violent. Rape almost becomes envisaged as a gift, which should be gratefully received. Indeed this dynamic is symbolised and materialised by each so called ‘transaction’. One may even wonder, had there been no crude act of violence or no report of women and girls being tied-up, whether the term rape might even have been used at all in CAR.

Under colonialism African childhood and womanhood were aggressively denied as part of a conscious effort to dehumanise. Remnants of this system of oppression continue to shape the treatment of black people today, with those at the bottom of the hierarchy of blackness, being the most disposable. Indeed, the impunity which surrounds the abuse by western men of third world black bodies exemplifies this. Speaking of ‘transactional sex’ is, therefore, both a vehicle for old colonial notions and a way for predatory peacekeepers to resist accountability for their rape and sexual exploitation of children and of vulnerable women. However, given that recent evidence suggests almost half of the British public sees colonialism as something to be proud of and, that about a third consider that ‘we talk too much about the cruelty and racism of Empire, and ignore the good that it did’, then no doubt mass murder/mutilation can be offset against any purported ‘economic development’. Under this logic, perhaps being given a mobile phone can be seen to constitute consent and even rape can be offset against ‘lifestyle improvements’.

Guilaine Kinouani is an intersectional feminist, an equality consultant, a therapist and writer. Her analyses are rooted in her social location as a Black French woman, a migrant, and a (proud) child of the Banlieue with solid roots in Africa. She is currently completing her doctorate in Clinical Psychology.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence