‘No to Block 28!’ Indigenous and peasant communities are fighting to protect nature and their way of life in a remote corner of the Amazon

By Andrés Tapia. Published 4-21-2021 by openDemocracy

I grew up in the Ecuadorian countryside. My first memories are from around 1990, when my family and I were living on a 28-hectare farm, a pioneering conservation project in the tropical rainforest.

Often, I would sit with my sister on the front steps of our house, gazing at the “blue mountains”. It was my father who coined that phrase, after their distinctive colouration. Decades later, while studying field biology at university, I learned that these were the subtropical Andes. Specifically, the Abitahua Protected Forest of the Llanganates Sangay Ecological Corridor, a transition area (also known as an ecotone) that connects the eastern slopes of the Ecuadorian Andes with the Amazonian lowlands.

At home, several stories and legends were told about these mythical mountains. Many have tried to navigate them, inspired by tales of pre- and post-Inca treasure, as well as their fauna and flora. As a young man, I was told that few people had succeeded in exploring the mountains, or at least had told me of their experiences of doing so.

After the legions of explorers, several biologists and researchers went into the jungle – and discovered one of the greatest areas of biodiversity on the planet. The territory’s biogeographic characteristics have given rise to a great variety of habitat types and microclimates. It boasts a very high endemism of species, as well as abundant bodies of water: springs, streams and rivers that descend through the foothills.

For this reason, the area is currently considered a biodiversity hotspot, one of five of its kind in Ecuador, along with the Galapagos Islands, the Equatorial Choro, the Cuyabeno Lagoons and Yasuní National Park. In 2002, the WWF declared the ecological corridor a ‘Gift to the Earth’, the highest award that the organisation gives to conservation projects.

The mysterious blue mountains of my childhood turned out to be a treasure of biodiversity for the whole world.

An intrinsic relationship

I grew up and learned about caring for nature thanks to a pilot programme (Fatima Experimental Center) for the conservation of Amazonian fauna run by the Organization of Indigenous Peoples of Pastaza (OPIP). Today, Pastaza Kikin Kichwa Runakuna (Pakkiru – the current name for OPIP, my home organisation) consists of more than 180 grassroots communities and 13 associations, communes and villages within Ecuador’s Pastaza province.

In 1992, the historic Allpamanda, Kakwsaymanda, Jatarishun march led by OPIP reached Quito, Ecuador’s capital, and obtained 1.3 million hectares of tropical forest for the Kichwa, Zápara and Shiwia nationalities. This included not only the mountain ranges of Abitahua and Llangantes, but also the great plains of the lowland jungles, which have been historically inhabited by Kichwa men and women.

I grew up surrounded by these stories and experiences, imbued by the spirit of the collective struggle of the runakuna (the Indigenous inhabitants of the jungle). These people have an intrinsic relationship with their natural environment.

The Kichwa, and all Indigenous nationalities in general, also have a fundamental relationship with water. It not only supplies their basic physical needs, but is part of an intimate spiritual relationship, because they believe that supais (the immaterial beings and spirits of the forest) inhabit aquatic ecosystems.

A matter of life and death

The headwaters and springs of these countless rivers in the town of Mera have also become a source of sustainable income. People survive in this corner of the Amazon because these of clean waters, perfect for rafting and much sought after by tourists, which are not found elsewhere in the region.

The income generated by ecotourism is highly valued, and means the local population as a whole is very keen to adopt and promote conservation efforts. The men and women of the forest, whether Indigenous or peasants, have a long-lasting familiarity with and deep knowledge of these remote territories, such is the strength of their relationship with the rivers and the forest.

This strengthens their determination to prevent any alien culture from threatening the waters of these rivers. We have grown up in them, we have learned to swim in them, we know their trails and have used them to master orientation in the jungle.

So, for us, fighting to keep the blue mountains alive and free of oil, mining or hydroelectric exploitation, is a matter of life and death.

Threat from oil companies

But this biodiversity hotspot hides a resource coveted by very powerful forces: oil. In November 2014, Ecuador’s secretary of hydrocarbons launched the bidding process for oil ‘blocks’ in the south-eastern Amazon. Block 28 was awarded to a consortium formed by the state companies Petroamazonas EP (Ecuador, 51%) and Belorusneft (Belarus, 7%) and the private company Enap Sipetrol (Chile, 42%).

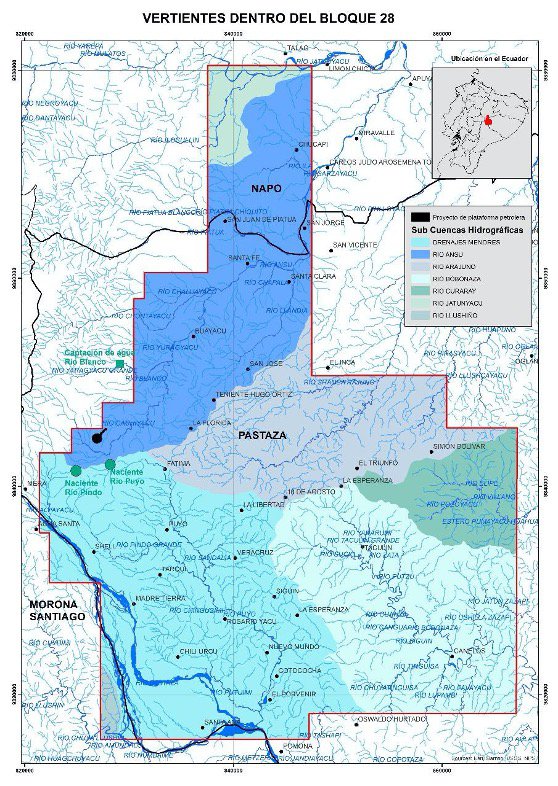

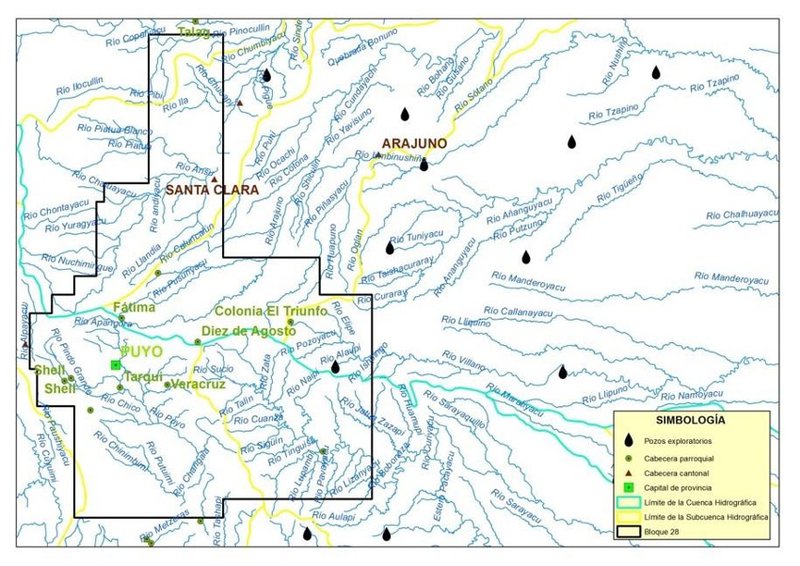

Block 28 covers an area of 175,250 hectares, 97% of which is located in Pastaza province, and contains estimated oil reserves of 30-50 million barrels. Expected costs are $25-30m for exploration, and $375m for exploitation.

This directly affects the lands of the Kichwa peoples, which includes more than 73 Indigenous settlements and 43 peasant communities. Water resources are the most affected, mainly the headwaters of the Napo and Pastaza river basins, the sub-basins of the Anzu, Arajuno and Bobonaza rivers and the micro-basins of multiple rivers.

We need water to drink and fish for our food. Water (or yaku) is also the essence of the spiritual energy of the runakunas. Yaku feeds our mythology, the magical and cultural patterns that we have grown up with.

Communities fighting back

Delimitación del Bloque 28 en Pastaza

Representatives from Petroamazonas have arrived in Block 28, with offers to develop local infrastructure and settlements. But they don’t care about the reality of the communities and their relationship with the natural environment that surrounds us in the Amazon, especially in the high mountains of Pastaza.

For this reason, everyone in Pastaza is in a state of alert. Indigenous peoples, peasants, mestizos, tour operators – all are fighting under the slogan “Flow like water. No to block 28”.

Our population has issued a manifesto, declaring that water and other natural resources are not up for negotiation with any oil company. We are defenders of water, and our lands are the source of the main water basins that feed the great Amazon River: we will defend it to the very end.

Según nuestra cosmovisión, en los ecosistemas acuáticos habitan seres inmateriales, espíritus, dioses, supais (seres inmateriales y espírtus del bosque) y otros | Andrés Tapia

We are determined to show the world the importance of this biodiverse area and the damage that will occur from oil extraction. It will destroy the water and life within our blue mountains. We want to raise awareness in all corners of the world; we want the voice of the communities that have decided to say ‘no’ to oil exploitation to be heard.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence