“This moment of crisis for the country’s schools,” says the co-author of a new report, “could be a turning point.”

By Kenny Stancil, Published 2-5-2022 by Common Dreams

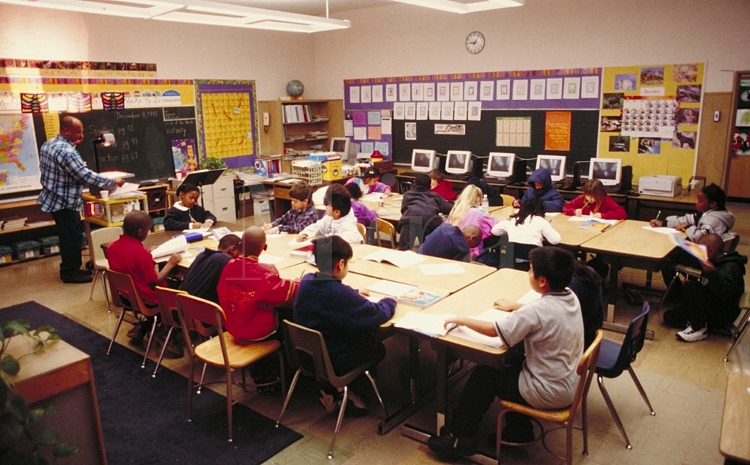

Photo: Foxy1219/Wikimedia Commons/CC

A new report out Thursday documents growing staffing shortages in public K-12 schools throughout the U.S. and makes clear that the crisis cannot be solved without raising pay and investing in the education workforce—starting by using unspent federal Covid-19 relief funds as a “down payment.”

According to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), which first presented its research last week to a task force of the American Federation of Teachers, employment in public elementary and secondary schools decreased by nearly 5% overall from fall 2019 to fall 2021. The number of people employed as teachers fell by 6.8%, bus drivers by 14.6%, and custodians by 6%.

Almost every state has experienced a substantial decrease in public education staffing during the coronavirus pandemic. According to the report, the largest declines have occurred in Alaska (-17.5%), Vermont (-11.6%), and New Mexico (-10.7%). A total of 16 states have experienced losses of 5% or more, with seven states seeing losses of 8% or more.

Health concerns are one significant factor likely fueling nonteacher staff shortages. As the report explains, “education support staff tend to be older—and thus more at risk of severe Covid—than the average U.S. worker. Less than a third (31.6%) of U.S. workers overall are age 50 or older, compared with 66.2% of bus drivers, 55.4% of custodians, and 50.4% of food service workers in the K–12 public education workforce.”

Another key issue likely driving support staff shortages is the extremely low pay. “From 2014 to 2019, the median weekly wage (in 2020$) for food service workers in K–12 education was $331, while school bus drivers received $493 and teaching assistants $507,” states the report. “In contrast, the median U.S. worker earned $790 per week.”

Inadequate pay is also “a long-standing issue for teachers,” the report notes. “Past EPI research shows that public K–12 school teachers are paid 19.2% less than similar workers in other occupations.”

The good news, a summary of the report points out, is that “many states and localities confronting shortages right now have more capacity to address funding and pay issues than they have had in decades. Congressional pandemic relief measures have provided unprecedented levels of federal funding to states, counties, municipal governments, tribal territories, and school districts.”

David Cooper, co-author of the report and director of EPI’s Economic Analysis and Research Network (EARN), said in a statement that “public officials should seize this moment of greater fiscal flexibility to begin making the reforms needed to attract, keep safe, and retain high-quality teachers and support staff.”

“That means raising pay, enacting strong Covid protections, investing in teacher development programs, and finding ways to support part-time and part-year staff when school is not in session,” said Cooper.

In addition to tapping into hundreds of billions of dollars in available pandemic-related aid, policymakers “also need to plan for sustainable long-term investments in the K–12 public education workforce,” says the report, which stresses that this will require expanding state and local revenues through progressive taxation.

As EPI’s summary notes:

The current gap in K–12 education employment comes on the heels of huge employment losses in public education after the Great Recession that were never fully restored. Previous EPI research has shown that budget cuts, lack of investment in schools, low relative pay, challenging school climates, and inadequate early career supports led to rising teacher turnover and a shrinking pipeline of qualified teachers in the country’s schools long before the pandemic began.

Among other things, the pandemic has demonstrated that “continuing to underinvest in public education… is not tenable if we want schools to be open and children to have a safe and supportive place to learn,” EPI adds.

Sebastian Martinez Hickey, co-author of the report and research assistant at EARN, argued that “this moment of crisis for the country’s schools could be a turning point—when communities begin funding schools at the levels required to recruit, train, and retain high-quality educators and support staff—but it will require public officials to choose to make those investments.”

“Federal Covid relief funds offer a down payment on these investments,” he added, “but making them sustainable will require an overhaul of how many states fund schools.”